Earlier this year I edited a book for Red Letter Christians called Jesus & Justice. What follows is a brief presentation I gave to ministers and others at South Wales Baptist College in Cardiff. It has been tweaked in the light of pre-election announcements!

My second chapter was a late entry into the book. We knew we would be publishing in an election year and it seemed to me that we couldn’t avoid talking about some broad policy issues. In the chapters on education and justice, there is quite a lot of reflection on how our society educates its poorest children and treats those who break the law and what all that has to do with justice. There are chapters looking at the consequences of economic injustice — in housing and people whose lives are touched by prolonged poverty.

So I thought the issue of economic justice needed to be tackled head-on.

And one of our dialogue partners, Chris Shannahan agreed. He has just completed a three year study of the effects of austerity in Britain called Life on the Breadline. The full report will be out next year but you can get a good glimpse of the findings on the project website (Home – Life on the Breadline (coventry.ac.uk). They do not make for happy reading.

Shannahan observes that while the church has led the way in good works — food banks, night shelters, and the like — and is ok at advocacy on certain issues, it has been nervous about getting involved in the politics of austerity. He says,

‘Until we find a way of marrying bottom up and top down, the political and the welfare work, the political and the personal, the political and the spiritual, we are going to be missing the boat’

That’s from a part of the dialogue that didn’t make the cut into the book — shame! Blame the editor!

Hence my chapter, ‘Can we Tax our Way to Justice?’

The topicality of the chapter was illustrated this week. The Tories are planning to double the child benefit threshold to £120,000 per household. It will cost about £1.3bn. For the same sum the two child cap on universal credit could be scrapped, something that would lift tens of thousands of children out of poverty. Elections are about choices: do we use the tax system to reward the well off (the latest Tory plan benefits the top 20% of UK earners) or alleviate poverty for those at the bottom of the heap? Can we tax our way to justice?

The chapter narrates my life as a financial journalist and then as a minister in Peckham helping to steer a large employment and regeneration charity through the 90s and then into my NT research and how what I was discovering about Paul was landing in our context.

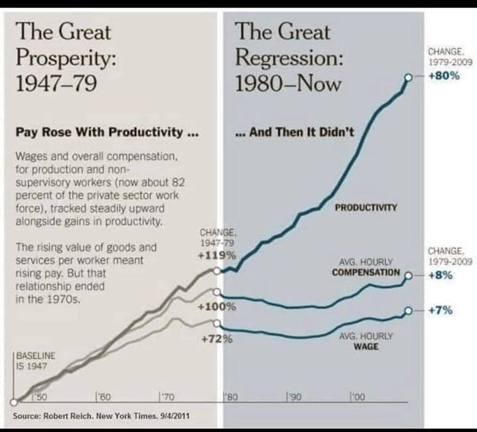

I started my working life in 1979 just on the hinge point of the graph above, charting the rise of neoliberal economics through its calamitous first decade. I wrote about big bang in the city that unleashed a financialised capitalism on us that eventually led to the financial meltdown of 2008 and the austerity that has gripped Britain ever since

As chair of Pecan, the charity I mentioned, I presided over an organisation that operated an equal pay policy. Every member of staff from the chief exec to the receptionist and creche workers were on the same pay. It was a model derived from the parable of the workers in the vineyard. At a time when executive pay was taking off into the stratosphere, I like to think Pecan modelled a viable alternative.

But it was the crash of 2008 that brought into focus the chronic inequality brought about by slashing tax rates for the wealthy and cutting benefits and other welfare provision for the poor; a gulf that has only widened over the past 14 years.

I’m with Chris Shannahan, I think as church leaders we need to be talking and doing politics.

So in 2022 I wrote a blog called ‘who would Jesus tax?’ reflecting on sensible proposals from the Tax Justice Network to tweak the current tax system without touching income tax and national insurance.

The tax debate needs to be broadened to include the wealth of people and not just their income. Simple changes such as equalising capital gains tax and income tax rates could raise £14bn, applying National Insurance to investment income would yield a further £8.6bn. Add to this a 1% wealth tax on assets over £10m and another £10bn could be raised. These changes combined with other tweaks of allowances could swell the government’s income by £37bn, a significant wedge of cash to be spent on public services and raising benefit levels for the poorest. And this is not just a one-off; this is annual new tax income.

The deeper question, of course, is what this has to do with the church, with Christian theology.

And for me the answer starts with Paul. My Master’s dissertation on Paul argued that he was a community activist creating small groups across the cities of imperial Rome that practiced radical economic sharing as a sign of the Kingdom’s coming. And a good place to start a reflection on Paul’s contribution to all this is Gal 2:10.

Here Paul wants to nail down the essentials of the gospel for his first hearers. And there are two of them. Faith in Jesus – the central pre-occupation of the letter – is clearly one of them. But something else is mentioned here as being essential: remembering the poor. Paul and his team had come to Jerusalem with a gift for the Judean Christians from their Gentile brothers and sisters in Antioch precisely because Paul was already keen to remember the poor.

The gospels of Antioch and of Jerusalem were the same not only in content – membership of God’s people came by faith in Jesus and nothing else (2:15-16) – but also in consequence: that the poor were remembered, that any expression of community among Jesus followers involved a radical economic focus on the poor. Remembering the poor, regardless of ethnicity, becomes a touchstone of the truth of the gospel that Paul is defending in Galatians: faith in Jesus alone means we are part of one family under God responsible for one another’s wellbeing – both spiritual and material.

So, Paul’s gospel motivation was ‘to remember the poor’ not aspire to be rich, his focus is downwards rather than upwards; so in Romans 12 he urges us to look ‘down’ to the poor not ‘up’ to others who might benefit us economically. The truth at the heart of this movement has everything to do with this downward mobility: ‘remember the poor’ (Gal 2:10) is worked out in 6:9-10, forming a sort of inclusio around the economic ethics of the letter (in some way spelled out from 5:1 onwards in terms of love), just as 1:4 and 6:14-15 form an inclusio around its eschatology: this foolish economics is dependent on God’s new creation coming through the resurrection of Jesus.

Paul’s understanding of how this worked was rooted in his tradition reinterpreted through the cross and resurrection of Jesus.

The Sabbath cycle consisted of weekly rest, a seven yearly rebalancing of economic life, and a fifty year fresh start (that is after seven ‘seven year’ cycles) that saw all debts cancelled and property (especially land) sold because of hardship, restored to its original owners.

This cycle aimed to ensure that Israelite society was not ruled by money and no one became permanently destitute.

It was a model for equality: sabbath puts God before work and wealth: in the creation story in Gen 1:27-2:1 people are created to work as God’s stewards on day six but on their first day (day seven) they rest, as they do every week. Every seven years the land is to be allowed to rest (Ex 23:10-13; Lev 25:2ff), slaves released (Deut 15:12-18) and all debts cancelled (Deut 15:1-6): no one, however feckless, was to be left in debt or slavery for any longer than seven years. Then every 50 years everything was to return to how it was when they entered land (Lev 25:10-16). No family could ever lose the land that they had been given by God whatever had happened in the intervening 48 years.

It was a mark of faith: the sabbath cycle was a visible sign that God’s people lived differently to the rest of world, trusting that God was giving a land of abundance for all to enjoy. It was so serious for God that failure to live this way resulted in exile: Isa 1:10, 17; 3:13-15; 5:1-8; Jer 34:16-22; Ezek 16:48-50 (see also Neh 5:1-13).

And it lands in the New Testament: when Jesus comes, he proclaims jubilee (Luke 4 quoting the great jubilee texts of Isa 58 & 61) as the foundation of his programme. His teaching on money embodies it – Luke 12, 16, etc.

And the early church instinctively practices it – Luke in Acts 4:34 echoes Deut 15:4. Little wonder that Jesus and his movement is seen as good news for the poor – money’s power is broken, its yoke removed, bellies are filled and all are loved by God into his Kingdom!

And then I found that giant of the world of New Testament scholarship, John Barclay kind of agreed with me.

He is currently working out how his renewed emphasis on grace in the theology of Paul lands in the world in which we live. I can’t wait for the book to arrive. But I had a taster in Spurgeon’s post-grad seminar last year. He says,

Grace functions as an ‘iconic paradigm, an exemplar of how we might rethink some of the core characteristics of economic relationships.’

He continues,

That giftedness of all things and all persons (given, as it were, to each other) has significant implications for how we conceptualise ownership and possession. In modern, Western society, we have naturalised a notion of private property by which individual property rights are regarded as supreme: what I have is my own, and if I choose to share it with someone else, that is a voluntary act of charity, not an obligation or an inherent character of the goods I share.

He adds,

“God is able to provide you with every gift in abundance … so that you may abound in every good work” (9.8). The theological instinct is to enquire not what I can amass but what can I share, not, as we shall see, in a mode of self-depletion, but with a view to mutual enrichment through conjoint benefit.

And so it goes on. I hope the paper will see the light of day soon and the book in due course. It got me thinking about how Pauline economics lands in our advanced capitalist world. In another bit of the dialogue between Sally, Chris and me that didn’t make the cut (it was a very long conversation!), I said,

Pauline economic mutuality comes out of two things. One is the Old Testament roots of the Sabbath cycle, and the fact that God is a God of abundance and everything we have really still belongs to him. But the other thing it comes out of is the mutuality of the back streets of Roman cities, where craft workers would mutually support each other. So there’s something profoundly spiritual, and Jesus revolution about it. But there’s also something that just comes out of the culture. But the problem in translating that into advanced post-industrial Western contexts is that, like it or not, we have bureaucratised pretty much everything, including people’s welfare. You could argue that the origins of the Welfare state lie as much in Methodist as in Marxist thinking at the end of the nineteenth century. It was about, how do you translate mutuality into public policy.

And so a welfare system was designed to ensure that there was a safety net, that people did not fall into such devastating poverty as they did in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, because they would be rescued by the distribution of income to the very poorest. So it was a bureaucratic way of, in a sense, earthing and expressing something that might owe its origins to a Christian understanding that those who can’t actually meet their weekly bills. need support from society to meet those bills.

That society might have been the local church and it worked very well in preindustrial contexts. But as we become more industrial, more bureaucratic, this is a fairly simple way of putting it, but as we become more distant from each other socially and communally, it becomes the role of the state to step in and do what communities used to do.

And I don’t necessarily think it’s an either, or; I think it can be both/and. But I don’t think the State can say, well, actually, this is all down to local communities getting together and bailing each other out (as in a lot of chapters in the book) because I think there is a responsibility on the part of the State, the collective ‘us’, to do what needs to be done, which is why I talk about changes in taxation that might lead to there being a better distribution of wealth that can be used to overcome a measure of economic disadvantage. Taking issues with Trussonomics, I think there is a distribution problem that could be partially solved by a more just tax system.

As Chris Mullin says, ‘taxation, fairly raised and efficiently used, is the subscription we pay to live in civilisation.’ I agree. And I would add that it is sub that every citizen owes and should pay to create and sustain that civilisation.

I conclude my chapter with this observation,

Some people wonder how my seven years as a financial journalist prepared me for ministry. I now see they were a key part of the journey, an essential course in the skills required to seek the shalom of the city through a life of activism and advocacy. The things we do locally as gatherings of Jesus followers, we do to model a different form of economics, a way in which money can work for the common good (click). But we cannot stop there. We also need to press government to see that this works and that justice can be fashioned by policies based on these insights. It is what Jesus called me to on that sweaty night in 1977 and what I have tried to pursue ever since.

Leave a comment